The "pros" involved no longer needing to worry about money, no more stress about the future and not having to finish the project I'd been procrastinating on. The "cons" were — well, there weren't any that I could think of.

I'd been constantly fantasizing about killing myself for the two weeks prior. I had been on medication for depression for two and a half years — I took pills three times a day — but after moving to New York City in August I stopped taking them.

Not on purpose; I ran out of refills and didn't have a doctor, and things went fine for a couple of weeks so I thought I'd just wing it.

And then things weren't fine anymore, and I was crying in the bathroom, trying not to cry while walking down the street, and forcing myself to stay away from busy street corners.

So, with tears in my eyes, on Oct. 11, 2015, I left the restaurant I was at with friends and started walking aimlessly down the streets of Brooklyn. I was crying again, this time deep sobs that made my body shudder. I sat down against a wall and watched the traffic, trying to build up to the right moment, the moment I would do it.

A truck trundled toward me.

This is it, I thought. This one, right here. Let's do it.

I waited too long and missed my opportunity. I kept crying, and then I went home.

The next evening I was in the hospital. A doctor thought it wouldn’t be safe to let me go home when my suicidal feelings were so strong.

I’ve dealt with depression and suicidal thoughts for a long time. I started seeing a counselor in 10th grade because I hated myself so much I was barely able to function much of the time. A few years later, I started fantasizing about killing myself. I thought it was in the world’s best interest for me to die, so I could stop hurting the people I loved the most.

In October of 2012, during my second year of college, I tried to kill myself for the first time. I took my scissors and phone to a reservoir on campus and promised God that I would kill myself unless someone texted me to tell me they loved me.

And I waited.

I cried.

I swore.

I waited some more.

And then, I swear to you, I heard God. He told me that His love needed to be enough.

I put the scissors in the trashcan and swore that would be the last time I thought about suicide.

It wasn’t.

Barely four months later, around Valentine’s Day 2013, I was hospitalized again. In October of 2014 I tried to kill myself yet again.

All of which led up to my hospitalization two months ago. I missed a full week of graduate-level journalism classes, of my work as a tutor in the second grade, and of Instagram and Twitter.

I spent the week getting back on my medication, sleeping a ton, and letting myself slowly feel better. I made friends with my fellow inmates — I know I shouldn't call them that, but it's a leftover habit from my first hospital time, which felt more like prison than healthcare — and even did homework at one point.

And exactly one week after I was admitted, they let me go. They walked me to the door of the locked ward and released me into the wild.

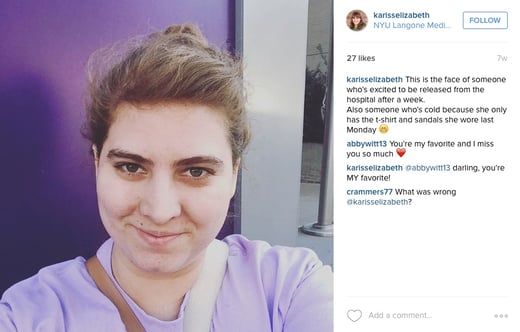

So of course the first thing I did was post a picture on Instagram.

People loved the picture because it seemed to show that I was happy. That my shadows and demons had been eradicated and I was home-free.

Which, at the time, I thought was true.

It wasn't.

The Instagram photo Karis posted after being released from the hospital. (Source: Instagram.com/karisselizabeth)

The Instagram photo Karis posted after being released from the hospital. (Source: Instagram.com/karisselizabeth)

Just a few days later I found myself wandering around at night, wishing I could call someone and cry and tell them that I was thinking, again, of hurting myself. Two weeks after that the depression was so thick I missed work in the morning. I couldn't get up. To this day, I have moments of severe depression where I wonder how I’m supposed to function.

But as I’ve thought about my situation, I’ve realized something: The hospital isn't a magic pill. And neither are the actual pills I take.

Depression doesn't go away because I wish it so or because I spent a few days in a psych ward. It doesn't vanish if I don't believe in it or skitter off if I yell loud enough. It's persistent and sneaky and it's something I'm going to have to deal with for a long time. The medication helps me control it. My faith in God helps me withstand it when it comes back. I've got a motto — "He is here." It means I believe in God's presence all the time, even when I can't see it.

The hospital saved my life when it was in danger. Medicine and God are working together to save it every day. It is possible to survive depression. It's even possible to survive being suicidal, and attempting suicide.

The night I made the list of "pros" and "cons," I missed something very important in the "con" column. The bad thing about killing yourself is it takes away your chance to live. It takes away the opportunity for you to succeed, to dance, to laugh, to sleep in on slow Saturday mornings, have your first kiss with that attractive boy you have a crush on or enjoy a rich, decadent dessert. It keeps you from doing the things you love.

And the "pros"? They're not worth losing all of the above. They're not even real. That's just the depression messing with you.

I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’ll most likely deal with depression my whole life. And I finally understand that depression isn’t a death sentence.

Karis is a grad student at NYU in New York City. Here writing has appeared online with Seventeen as well as Good Housekeeping. She blogs at karisrogerson.com.

If you’re struggling with thoughts of self-harm, there is hope. You can call 1-800-273-TALK to chat with someone about it. For a list of other resources, visit the website of To Write Love on Her Arms here.

Struggle with self-esteem? Watch Michelle's story.

(Source: Dollar Photo Club)